Here's to widespread justice!

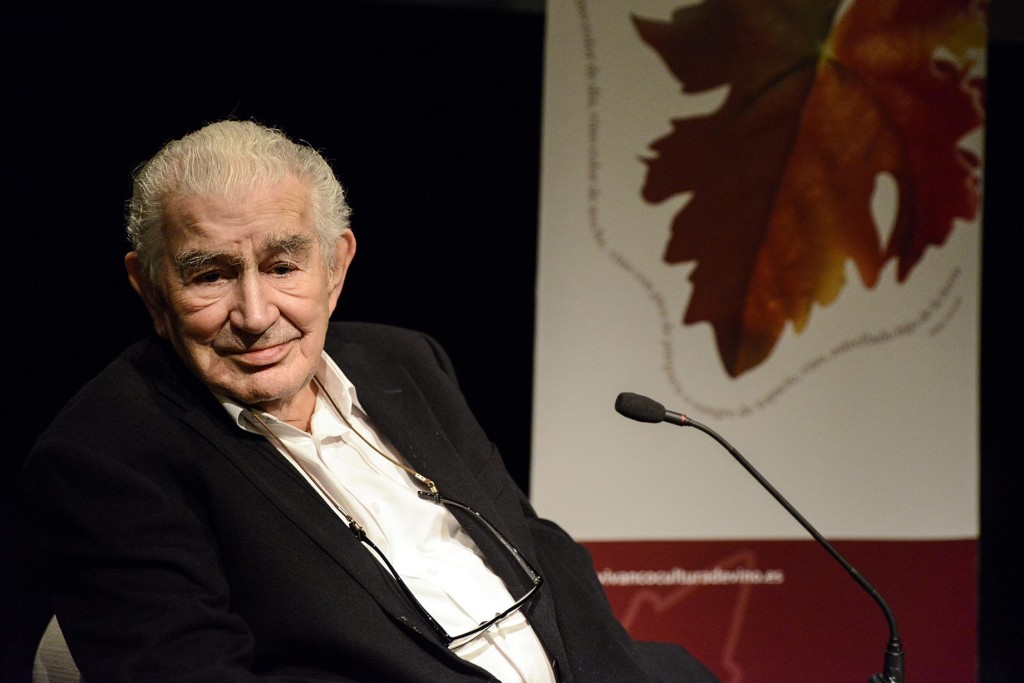

Antonio Gamoneda, in sips

By Lali Ortega Cerón

If my work helps my readers to make a living, I already feel very rewarded.

The day dawned cold in León. Just a few hours earlier, Don Antonio Gamoneda, wrapped in the night, was finalising some notes on his writings. To look at the autographed poems of the 2006 Cervantes Prize winner is to venture into a kind of angular hieroglyphics that allow us to guess the exceptional nature of one of the most important living poets of the last half of the 20th century. It is not for nothing that this author of 2 narrative books, 12 essays on art and literature, 5 audio or audiovisuals, 4 works with musical composers and 45 books of poetry, is Doctor Honoris Causa by 5 Universities; Prix Européen de Littérature or Premio Reina Sofía de Poesía Iberoamericana, both also awarded in 2006.

Age keeps this tireless writer active, who is depressed by idleness. It won't be my turn for the time being, he declares with impetus! His voice is low. Pleasant. Naturally kind. His smile can be glimpsed in the melodious cadence of his sentences, in the musicality of a tempered and sincere discourse in which the absence of tension and rancour is appreciated in these times.

The window of Don Antonio Gamoneda's office adjoins a courtyard with some small trees "that are very comforting to see" and two beautiful trees: an uncommon evergreen lauroceraso. And a walnut tree. I ask him about his library, which I suppose contains the only book his father wrote, Another higher lifea poet close to modernism who died in 1932, when his son was not yet one year old. An orphan marked for life who, paradoxically, learned to read, to live, to write, with his father in his hands. "Oh the library! It's not a marvel, because I ordered the books, but suddenly I had an attack of sciatica." And he laughs... "Now they're stacked, so they don't move from there." Like me, who would try to avoid the distant noise of a mower so as not to disturb a single nuance of this conversation with Don Antonio Gamoneda: the intense writer who still remembers and who, although he doesn't have all the answers, offers, among his thoughts, a serene shelter from the inexplicable.

León, November 2018. What returns your gaze to the outside, to the world?

A great restlessness. A world emptied, as we might call it, of humanistic and humanitarian projects. Of behaviours and ideologies that may be necessary, but which do not seem to be put into action, quite the contrary. This uneasiness is creating in front of me and I try to tell myself that the world is certainly in a disturbing attitude, in a disturbing disposition. We have to hope that the younger generations will make it a little better for us.

And what does he see inside himself, at 87 years of age?

Many memories. A horizon in front of me, without any drama, which cannot be a horizon with long distances; nor much time; nor much space. I am an older man and above all I see that there are many aspects of my vocation and my creative need that I have not been able to do in my life. And of course, I try to make up time, which is not always fruitful. Anyway, that's how it is. And naturally my attitude towards this is an acceptance that does not lead me to passivity, to disengage myself from life, from my own life and from the life of those around me (and if I hurry, from the life of all human beings). Nor of my vocation, of course.

What has been your taste of life for almost a century?

That transit of mine for so many years has been hard, not only for me, but to some extent for the historical planetary population. But I would like to think that in some ways, on the whole, we are perhaps a little better off, despite the hardship. In the sense that our environment and our prospects, collectively, are better than a person my age might have been at the beginning of the last century.

What about the feel of a blank page?

Touch, inseparable from sight, suggests to me the need to pick up a pen, so that the page will no longer be blank.

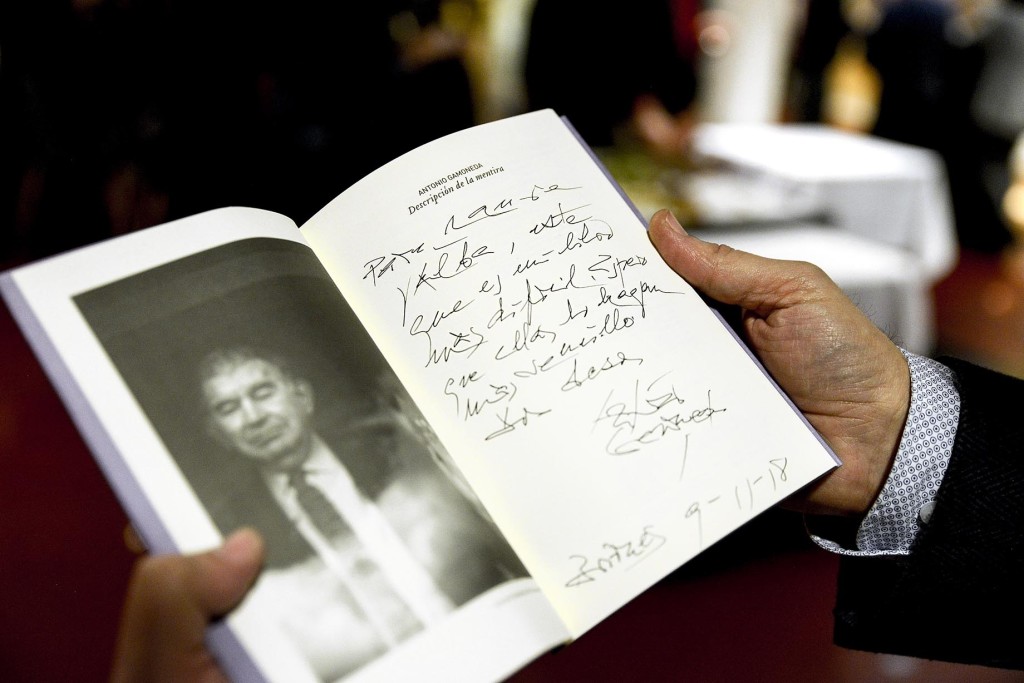

Description of the lieWhen you hear them, what do they inspire in you, both pious and superlative?

It is indeed an interesting distinction. A pious one is sometimes even desirable, if it will prevent a person's suffering. The lie, which, with that exception, places us before a false horizon and is neither necessary nor advisable, is to be rejected. In the book I referred to the great lie (it was published in 1977) that Spain, possessed by a dictatorship, went through for more than 40 years.

His first memory of wine...

Ah, let's see, let's see. Well, yes, he's not very good (he laughs). I was a little boy of 8 or 9 years old. They took me to a grape harvest in a nearby village and left me under an awning. People went to work. I was there, bored. Next to it was what in León is called a "pajoso", a straw-wrapped pot (I left one at Vivanco, a small thing), a traditional product in the whole of the León plateau, used to keep the wine cool, claret, in summer. Well, a little boy... and I didn't know what I was doing. And I started to drink (he laughs) and I got really sick!

He learned to read and discover the musical cause in words, with the only book his father wrote: Another higher life. Rhymes and Legends by Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer was the second book that fell into his hands. The third, Second Poetic Anthology by Juan Ramón Jiménez, one of whose poems Antonio Gamoneda read aloud for the first time. These inherited verses were his primer in 1936. These were times of war, without schools, which gave Antonio Gamoneda his first difficulty and a lesson he learned to live with.

If you had been born in the 21st century?

The generally unfortunate circumstances of being orphaned shortly after my birth and the Civil War would not have happened. We were certainly poor. All my mother's small patrimony, after the journey from Asturias to León to cure her asthma, was lost with the war. The schools were closed. I learned to read from my father's book. Those circumstances are unrepeatable. If I had been born in the year one of this century... I think that with the same temperamental background, I would be a different person. It's something imaginary, because you can't think of yourself as someone else. What would I be like? What I answer you would be fantasy. We have already said that those were difficult years, hard years, years of suffering, but I cannot reject those years that have made me who I am. Their circumstances have shaped me.

Now we have all the resources and sometimes they are not used enough....

It is true, it is true. I see that young people, Spain in particular, are not very well off, but they are infinitely better off than me, a very poor 15 or 20 year old. Perhaps, in general terms, we are not very fortunate in the way we make the most of it. We allow ourselves to be invaded by technology, by consumerism, in a way that I think diminishes us, that automates us in a way. We stop being what we could be, with a finer instinct, by the use of what you certainly say: we have everything. I am not saying that technological advances are bad, but I am saying that the servitude that so much technology provides is bad.

What has marked you most as a life experience?

In other words, orphanhood and war. We were left homeless in this immense disaster and this left a mark on me, a way of being in life. Helplessness and poverty in the first years of my life. It is a mark that remains.

What has the absence of a father figure and a strong female world meant for you throughout your life, also as a father of three daughters?

Certainly the relationship of a widowed mother with an only child is very special, very intense, perhaps too intense. My mother, I think without knowing very well if it was good for my state of mind, in the present and in the future, made me feel like an orphan. I grew up with that notion. She put me in an order that as a writer, I have always said that my writing is conceived and developed in the perspective of death. This is the imprint. Nor can I imagine what the person would have been like if those terrible events had not relapsed. I try to be at peace with myself in terms of coming to terms with that and putting it into myself as a form of positive awareness for my present, my brief future, and that of those around me.

After this stage of your life, have you discovered the enigma, the meaning of life?

No, no, no. (Smiles). I don't think anyone has discovered it so far. I remain in that perplexity of not quite knowing why I am inside myself, here, right now... I don't know. What is to become of this world? I don't know either. I try to have a consoling idea, to think that this slow improvement of the existential circumstance will continue to progress.

As you are about to turn 88, what is essential to you?

I value for myself, for those who are close to me and those who are far away, to be able to be aware that my behaviour is positive, that in some way it is supportive and helps me to remain in this perplexity that is existence. A way of behaving. And look, I also wish for the right awareness and the right conscience, within this perplexity, in these people who are in the broad existence, also intergenerational.

Premio Cervantes 2006, Premio Nacional de Poesía (1988) for his book Edad, Premio Reina Sofía de Poesía Iberoamericana for his work as a whole (2006), Premio Quijote de las Letras Españolas (2009). What were the beginnings of Antonio Gamoneda like?

I worked in a bank at a very young age. Like any other poet, with the desire to have the time and circumstance for myself that would allow me to write and grow. I seem to have succeeded. I have friends, even many, but I have lived oblivious to the pettiness of the external circumstances of writers. And I am satisfied that I have done so.

And what was the turning point as a poet and writer?

I never thought I was either small or big. But there was no doubt in my mind that I had to write. I haven't needed much public recognition. I don't dislike them (he laughs), I have my vanity. I have my interests that could be called social, I don't despise any of them. But I know that recognition, whether it's awards or whatever, doesn't improve the quality of my poetry, or the rest of my writing. I value them, but I haven't sought them out, nor have they turned my life around. I have always had the need to write.

If you look back at the bulk of your work, how do you evaluate it? How do you react?

More incomplete than it should be. It's full of holes, but I'm trying to learn to conform. There seems to be no other way.

How does it feel to start and finish a book?

In poetry I feel a sense of liberation. To take a step, and that it is indeed of convenience for writing. A strong attention that remains for as long as it takes, a day, or ten years. And then release and rest... although later it seems that they were not so necessary.

What has the process of researching and remembering your life been like in order to write your memoirs?

An encounter with myself, where more memories dwell than I thought I had. As for the boy who goes through these memories... the old man who is there now, he finds it bearable. There is a kind of judgement of the writer when he has to evoke himself with the perspective of the years. The old man judges the young man before him. And that is there.

Can you recommend a title by Gamoneda?

Book of the cold.

One of his works is entitled Gravestones (1987). A few weeks ago I visited Westminster Abbey in London. In the south transept of the church is the Poets' Corner, with memorials to famous English writers, not just poets. William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Lord Byron, Mary Eleanor Bowes, Geoffrey Chaucer, Thomas Hardy, the Brontë sisters (Anne, Charlotte and Emily), Lewis Carrol, T.S. Eliot... I thought about how you would perceive such a special enclave, where it was even embarrassing to step on the ground. Everyone leaves their mark once they are gone. As long as someone remembers him, he lives on. Writers and artists have an advantage.

It is possible. What happens is that you don't have to attach great importance to that footprint either. One tries to make the best of one's project. Your imprint... if the work has a value for current and future readers, if it helps them to live, even if only a little, I feel very rewarded. As for the Abbey, there is no doubt about it, this concentration of illustrious men, of tombstones evoking so much work, is an exciting and also a very beautiful experience.

In connection with the great composer Haendel (naturalised English), also remembered in Westminster, how does music influence your life? Is your perception different when there are lyrics?

Music in its original state comes before thought in poetry. Rhythm carries with it the utterance of words and words carry with them ideas. But the original component is in the rhythmic. It is not a discovery of mine, Aristotle said it in his Poetics. I value music very much, in itself and in what is central to my poetic writing. Although I've been very deaf for nearly 30 years, with technology - in this I'm lucky because they're getting better and better at it - (he laughs). Music is in me, even if only in its rhythmic aspect. Music is great. Now, while I work, I listen to a record of medieval music, from the early days of polyphony, Gregorian music... I have been a music lover and I will continue to be one for the rest of my life.

On 9 November 2018 you starred in the VI Jornada Nacional de Poesía y Vino Fundación Vivanco, in front of a full house of loyal readers of your work. How does this type of audience influence you, in terms of their gaze and their reactions?

As little academic as possible, because of the personal flow between myself and my listeners. I feel very good when I notice that meaningful atmosphere of that relationship that comes and goes. I try to speak as naturally as possible and avoid too much theoretical exposition. In general, we get along very well.

How has wine inspired you during your visit to the Museum Vivanco of Wine Culture?

The museum impressively confirms what we can call Wine Culture. Data and ideas of the world that revolves around wine, from the purely personal or social interests of cultivation and elaboration, to the finesse in which these nuances can be seen, and even the state of expectation of the pleasant attention that wine can provide, without reaching any excess. Even the state of expectation of a pleasant attention that wine can provide, without reaching any excess. It warms our spirits!

A glass of wine pending?

Wine of conversation, understood as "sharing", with human beings who may well be poets who are no longer with us. I have my great references and I believe that some of them would drink the glass: San Juan de la Cruz, Lorca... and I would jump to America to drink that wine with César Vallejo. Those are the glasses I'm missing!

I read in an interview that he knew more about wine than poetry - he sets the bar very high!

Not quite. We all have to guess at things. I don't have the knowledge of an oenologist or a specialised taster, far from it. I distinguish qualities, origins, aspects of the wine, a bit of ageing, the nuances of Rioja, Ribera or a Chilean white, the qualities it leaves us with when we have taken a sip and the wine remains in our sensibility. He joked that in poetry we can guess everything and know nothing.