In several previous articles we have dealt with the profound relationship that has linked, for thousands of years, the culture of man to the Culture of Wine. Among other texts we can recall: Collecting and commissioned works in the Museum Vivanco, in which we talk about the desire to investigate the myths and rituals related to the production and consumption of wine, from which the Foundation Vivanco and the Museum of Wine Culture were born; Pablo Neruda celebrates the nobility of wine in Vivanco, about one of the most beautiful lyrical compositions ever dedicated to the ancestral drink: Ode to wine by the famous Chilean Nobel Prize winner; The symbolism of wine, from classical mythology to cinema, in which we deal with wine as a characteristic element of Mediterranean cultural identity.

This time we evoke the atavistic link between wine and culture through one of the most fascinating poetic images in world literature: Homer's "The Wine-Coloured Sea".

At the dawn of Western civilisation, navigation played a fundamental role. Thanks to the sea, the Greeks traded, founded colonies, exported their culture, fought wars and were sometimes shipwrecked. The sea is both feared and respected.

In the narrative of the legendary Greek poet Homer, the Mediterranean Sea represents a paradigmatic setting and wine often appears as a restorative food (after crossings and bloody battles) or as a ritual element (to celebrate pacts, alliances or sacrifices to Zeus or other gods of Olympus). The definition "the wine-coloured sea" appears in both the Iliad and the Odyssey - where it occurs several times - and has been interpreted as a description of that full-bodied purple-brown colour that the sea takes on when at the end of the day the sunlight wanes and the dusk fades, heralding the arrival of nightfall.

"The wine-coloured sea" in the Iliad

Among other Homeric passages in which this expression appears is Canto XXIII of the Iliad (Games in honour of Patroclus), where the hero Achilles looks out over the wine-coloured sea in one of the most solemn moments of the whole poem. Faced with the lifeless body of Patroclus, killed in battle by Prince Hector, son of Priam, King of Troy, Achilles weeping cuts off his hair and offers it to his dear friend (ready to be burnt according to ancient tradition) to take with him on the eternal journey.

Achilles with the court of King Lycomedes. Borghese Collection, Louvre Museum. Photo: Jastrow

"The wine-coloured sea" in the Odyssey

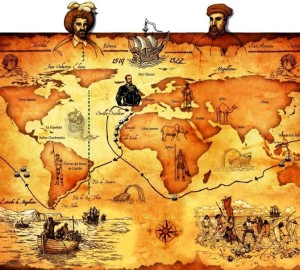

In the Odyssey, Odysseus uses this expression (among other occasions) in Canto VI (Odysseus and Nausicaa). Daughter of Alkinoo, king of the island of Scykeria, land of the Phaeacians, Nausicaa meets Odysseus on the beach, where the latter had arrived after the shipwreck of the previous day. When he wakes up, Odysseus tells her that he has survived the wine-coloured sea after leaving the island of Ogygia and suffering several storms for twenty days. Nausicaa takes him to her father and Odysseus (Odysseus) tells him of his adventures. The generous Alcinous provides him with the ships that will finally take him to his desired Ithaca.

Ulysses at the Court of Alcynoo by Francesco Hayez (1813-1815)

"The wine-coloured sea" as an inspiration today

After many centuries, this fascinating image continues to inspire scholars and writers all over the world. Just as an example we can mention the Classical Studies research group at the Center for Hellenic Studies at Harvard University (Boston), which publishes the Kosmos Society blog and has devoted several articles to the wine-dark sea.

Among the literary works that have been inspired by this fortunate poetic image is the magnificent story Il mare colore del vino (The sea colour of wine) by the Italian writer Leonardo Sciascia (1921-1989). Published in 1973, this story also gives the title to a book that compiles 13 stories about Sicily, the writer's native land. The book was first translated into Spanish by Ana Goldar as El mar colour de vino ( Ed. Bruguera, Barcelona, 1980). In the story, an engineer shares a train journey from Rome to Agrigento with a Sicilian family, consisting of a married couple, their two children and a young woman travelling with them. One of the sons, the most mischievous, is called Emanuele, nicknamed Nene. When, towards the end of the story, the train passes the sea at Taormina, the father, a schoolteacher, turns to the engineer and exclaims: "What a sea, where is there another sea like this?" It looks like wine", Nené interjects. And from then on, an episode between the ironic and the grotesque unfolds, in which the parents reproach the child, arguing with him about the colour that the sea may or may not have in reality. But Nené insists, categorical, with his affirmation: "It looks like wine to me" . The story ends with the thoughts of the engineer, who says to himself: "The wine-coloured sea, where have I heard that phrase? The sea is not wine-coloured, the professor is right. Maybe at first light or at sunset, but not at this time of day. And yet the boy has caught something real, perhaps the wine-like effect of such a sea. It does not intoxicate; it takes hold of the thoughts, it awakens an ancient wisdom.